|

This is my second entry in my series of different events I experienced that have shaped the way I see and interact with the world. Among the most significant is American Thought.

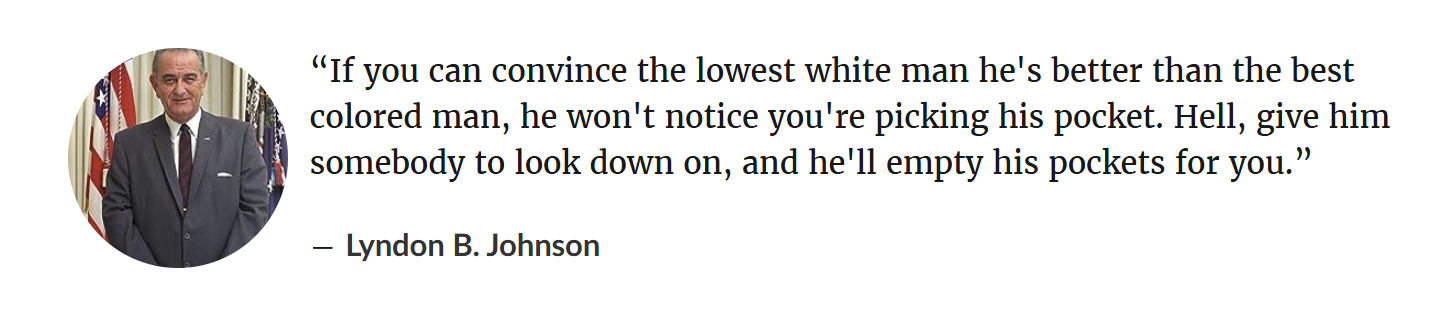

American Thought (AT), previewed in my previous entry, was arguably the most influential class I took in high school. At times, the class was hilarious and fun; other times, it was infuriating beyond belief. I didn’t learn a lot about American History or Literature, but I did learn a lot about people. It raised questions that I, as an outsider, was uniquely positioned to see. Hopefully, I am not alone in these remembrances and observations, but as I share this story, you will see why I suspect that this number is few. A few nuts and bolts before I dive into this tale. AT was the brainchild of two teachers: Mr. History and Ms. Literature, both of whom were politically liberal. The class was project- and discussion-based, and had an art component. For the discussions, we sat in a circle on the floor so that “everyone would be equal.” We called this a “kraal,” which is from Afrikaans. A handful of weeks into the school year, the art teacher was injured, so for many months, art was replaced with more kraals. As is common in any discussion-based setting, extroverts were praised, and introverts were criticized. (Years later, I met someone from South Africa and asked her about kraals. She said they were circular pens for holding goats. She’d never heard it used in the context of a discussion. This insight brought me joy.) Since the class was project-based, we didn’t have your typical assignments. Each quarter centered on a theme, and there would be various activities and papers, usually completed individually or in pairs. Then, each quarter culminated with a 6-person, 45-minute-long presentation. All assignments had two grades: one for substance and one for style. However, it was possible to get away with a lack of substance if one was entertaining enough. Conversely, if one’s main point contradicted a teacher’s personal view, even if well supported, one could get counted down. This brings me to third quarter. After a unit on Expansion (ie, colonization) and one on Industrialization, we were now doing “Isms.” You know, philosophies, like puritanism, realism, capitalism, creationism, transcendentalism, beat poetry, and the Southern mind. Yes, you read that right, the teachers of American Thought, a class that claimed critical thinking, made the decision to present an entire region of the country as a philosophical monolith on par with beat poetry and every other after-dinner debate in New England. I was not comfortable with this at the time, but did not have the capacity to fully understand what bothered me about it, other than it “othered” me on certain levels. Now, with almost 30 years of hindsight, I see how completely dangerous, divisive, and prejudiced that decision was. Before I go any further and tell the part of the story that really and truly makes me furious, I want to request one thing: Please remember that all the students in this story were around 16 or 17. I’ve had to give myself quite a bit of grace because much of my learning came later. At the time, I was too confused and jumbled to know how to respond. In the years that followed, different events would remind me of this class, adding clarity to both. I hope my classmates have had similar experiences of learning. Back to the story. At the end of the third quarter, one group chose to do their 45-minute presentation on the Southern mind. Specifically, they wanted to show the different stereotypes people in the Boston area have about the South. They had a video of one guy interviewing people in the grocery store parking lot, which was pretty funny. When he’d ask, “What do you know about the South?” many would reply, “South Boston?” They also performed a series of skits. None of them were flattering, but I only remember one. They did a portrayal of how the Klan got its start. The skit entailed the boys in wifebeaters, getting drunk and bored, then deciding to go beat up black people. There was a lot of laughter. I did not laugh. (Sidenote: I’d never heard of men’s undershirts being called wifebeaters before this sketch. I still hate this name.) When I got home and told my mom about this project, I just sobbed. I can remember where I was in the kitchen. What upset me the most is that they never presented how things actually are. Yes, it was a project about stereotypes, but what’s the point if they are never addressed? Take the formation of the Klan. It wasn’t bored, drunk rednecks. It was town and city leaders who thought they needed to protect their families. It had more organic and “noble” beginnings that are a lot more insidious and dangerous. The kind of thinking I believe is important for people to face if we are going to have the peaceful society that we claim to want. Gone with the Wind has a pretty good description of this kind of thinking, but according to Mr. History, that book was too biased to be referred to. Unlike every other novel we read. The bullshit shown in that skit actually perpetuates this idea expressed by President Johnson: So, yeah, that group got A’s for both substance and style. I never spoke up about my feelings about it because I was too confused at the time. Also, I’d been shut down a lot in the class. One friend who’d been in that group did ask me about it, and I did tell her it bothered me that they never got to how things really are, but the conversation never got that deep. She’s one of a handful of people I’d love to talk more about AT with because I know she, being one of two or three ethnic minorities, experienced things, too. All-in-all, I don’t regret taking the class. I learned a lot. Much of the experience set me up for success in later things I have done. But arguably little of what I learned was what they set out to teach me.

0 Comments

Learning to Pay Attention

I’ve written previously about what I like to call Experience Deniers, a term a friend and I coined for anyone who downplays the experience of another. Lately, with the world being as it is, this country especially, I’ve been thinking about how much the denial of others’ experiences has played a role in this mess. This goes in all directions. In truth, some of the most dangerous people I’ve encountered have been highly educated. The problem? They already knew everything and had nothing left to learn.

With all this, I’ve been thinking about how I’ve had the unique opportunity to live in the North, South, and Midwest. In rural and urban areas. Be amongst blue-collar workers and academics, predominantly white communities, and highly diverse ones. I’ve also traveled many places and have the kind of personality that quietly watches the interactions going on around me. I don’t know much, but I am curious, and I notice things and I ask questions. So, this is the first of a series of entries about different events I have witnessed or experienced that have shaped the way I understand the world and the way people interact within it. I believe all of these have made me a better listener.

I went to high school in Massachusetts. In my junior year, I took American Thought. It combined US History and Literature and met two periods a day. Having moved there from West Virginia and having family from Arkansas, I was the token Southern girl. As a result, my thoughts on the Civil War were immediately suspect, regardless of what they were. This was incredibly frustrating, especially when you consider how West Virginia came to be a state.

Anyhow, we read Uncle Tom’s Cabin. While I can respect the historical value of this book, I did not enjoy reading it at all. One thing I disliked was that the darker the Black people were, the dumber they were. It was like the amount of melanin was inversely proportional to intelligence. Yet, when I tried to voice this, the class – and teachers – responded as if the poor Southern girl just didn’t understand. Making matters worse, the discussion went on to the scene when the Ohio River freezes overnight, so Eliza can make her escape. The question was asked if this was something that could literally happen or an example of mystical realism. I answered that it was definitely mystical realism because I used to live on the Ohio River, and there was no way it could freeze overnight like that. Again, the poor Southern girl responses. It was pointed out that the much smaller river near the school froze over once when it was below freezing for several days. Never mind that the Ohio is the second largest river in the country by discharge. Never mind that where I lived was several hundred miles upstream from Kentucky, and it was still a quarter mile wide. Never mind that in the early 1800s no locks or other modern flow regulators had been built yet. I was from the South. They were from the North. There was no way I could know.

Autocorrect and the immediacy of most spellcheck software options make it harder to be a good writer. They overwhelm my already overloaded brain. I feel for folks with more intense speech and sensory issues than I have.

I am very self-conscious about typos. When I started this blog, and the one I wrote prior, I decided to not fret about them and just write. It took some stewing, but I eventually accepted that it would be hard for the same brain that made the mistakes to catch all the mistakes. I even allude to this in the blog description in the column on the right. Basically, for this project, the purpose is to get the ideas out, not to construct grammatically perfect paragraphs. It's been nice. I do proofread, but I give myself grace. Even though I face-palm occasionally when I look at old entries before going back in for a quick edit, I don’t regret this choice. I’m slow and shy to post as is. The added pressure of grammatical perfection would make all of this nonexistent. My insecurity about typos and grammar mistakes goes back to adolescence. It’s a combination of things, the first being that I generally caught on to things quickly at school. So, when I would make a mistake, I’d get reprimanded for being careless without much discussion of the root cause. The second was that I got the idea that I was a bad writer. I wrote about that in greater detail here: https://dorothyjeanrice.com/blog/slow-going. I now know that most of my mistakes are because I am more focused and interested in the ideas and how they flow together. Writing things out by hand, I often leave out words and sections of words. These are easy enough to address as I revise or transcribe. When I would write things on the board as a teacher, I made it a kind of game with my students when they would catch my mistakes. Used it as a way to normalize being a work in progress. Admittedly, none of this sounds that bad. I’ve recovered from most of my teenage doubts, and I am confident I can construct a clear, concise, and clever sentence. However, I do make a lot of mistakes. Since my brain got all spicy, the mistakes are more frequent. For example, when I first typed that earlier sentence, I combined ‘clear’ and ‘clever’ into ‘cleaver.’ I do this kind of thing when I speak as well. It’s minor and is easy to manage. However, the “Fix It Now” attitude of all these AI-driven programs adds another layer of things I need to manage. Remember when I said I want my main focus to be the ideas? It is really hard to sustain that focus when autofill is suggesting all kinds of ridiculousness, and every other word is being unlined. These distractions do not make me a better writer. The worst is when my words are changed into something I Do Not Want. A recent example is when I texted a friend something benign involving sperm. Autocorrect changed ‘sperm’ to ‘supermarket.’ I can’t even. That was so much of a train of thought killer, I don’t remember the original intent of the message. On previous occasions, I have changed the settings so that I can run a check when I choose. This is my ideal. (I also fare better when I am able to write out a draft by hand, but circumstances don’t always allow for that.) Unfortunately, the AI overlords do not like this, so every time they initiate an update, they undo this restriction and take over again. It is an ongoing battle. I once heard someone with a severe stutter talk about how frustrating it is to have people “help” by finishing their words for them. They described the way it interrupted their thoughts and said it actually makes the stutter worse. It’s better for them to push through. I feel the same way about AI writing assistants. On the days I’m struggling with words and language, I need to push. People and robots finishing my sentences make the problem worse. So, not only does AI bland and dampen creativity, but it can be an ableist jerk. Conclusion, like any other tool, AI is only as good as its user.

In early elementary school, I lived a few houses up the road from my best friend. Now I would describe her as a classic frenemy, but beginning in first grade, we were definitely Best Friends. We were both on swim team and could carpool. We had the same teacher in 2nd and 3rd grade. We were able to walk to each other’s house regularly. We had the freedom to ride bikes all over the neighborhood and meet up with other friends. Total besties.

However, there would be these inexplicable periods when I couldn’t do anything right. Like, without warning a recess I’d be greeted with, “Go away, Dorothy. I’m playing with Elle and we’re not your friend.” Then, a day or two later, it was like it never happened. I, being the good BFF that I am, of course forgave her. It was always confusing because I never knew what caused it. Also, “Elle” was rarely the same person and I don’t remember her, whoever she was, really being in on it much. All this hot and cold came to a head in the middle of third grade, when she went cold to the point of becoming full on cruel. Man, she was mean, and it lasted weeks. At one point I wrote her an apology note because I had no idea why she was so mad at me. She tore it up on the bus in front of everyone. Eventually, our teacher, thoroughly sick of us, sent us to the restroom to work it out. I remember shouting at each other before ultimately hugging it out. We made it through the remaining few months of school with our Best Friend status reinstated. Then, at the end of the summer, my family moved several states away. I bring this story up, because, about three years later, we moved back to that area. Seeing her again was actually a lot of fun. In our reminiscing, I brought up the Big Fight of Third Grade. She denied having any memory of it. My twelve-year-old self was floored and dropped pretty quickly, REALLY?!?! One of the most traumatic events of my childhood and the key second party claimed to have no memory?!?! My younger brother, who was SIX at the time, remembers how bad it was. That day, when I got back to family and told my mom about her lack of memory, I was sobbing. I didn’t understand why it cut so much, but man that sucked. Now I know the term gaslighting (great movie, by the way), and there is a lot of public discourse on how it is used as manipulation an abuse tactic. That’s not the goal of this blog post, though. Before I go further, I do want to pause to wrap things regarding my young frenemy. While I will never fully understand why she denied remembering our fight, she was 11, and 11 will 11. As for what happened in 3rd grade, from things my parents have said about her upbringing and my own adult perspective, she faced a lot of why-can’t-you comparisons. To be frank, my third-grade year was stellar. I was involved in some really stand-out extracurriculars that would take at least 257 blog entries to do justice. Even with how she treated me, it was by far my best school year. In conclusion, she’s not someone I wish to ever see again, however, I wish her well. Back to why I’m writing this blog: Those events were important because they heavily contributed to my decision not to let people get close enough to hurt me. As you may have guessed, that didn’t go well. Among other flaws, it turns out our brains are beautifully made with a limbic system and is intricately designed to manage and process emotions. It is anatomically separate from the more cognitive portions but integrated with overall network to allow for the processing of memories, motivations, and other complex thoughts. Like anything brain-related, we are only just beginning to understand how this all works, but this is one thing the scientists seem to agree upon when it comes to the function of the limbic system: EMOTIONS WILL BE EXPRESSED. We can only store them for so long, then they start coming out one way or another. In other words, we cannot choose to erase our own emotions. Lately I’ve been wondering how choosing to pretend events never happen affects the denier. In a way, it’s more rational than emotional, but since the limbic system contributes heavily to memory…? Is this why some people suddenly become overcome by guilt? Recent events have me wondering how erasure affects people at the cultural level. Think about it:

Now that I am at the end, I realize I needed to tell that story from my childhood to arrive at the following question: when you consider the way we are designed – our brains, DNA, trees, fungal networks, the interconnectedness gorgeousness of absolutely everything – how could history possibly be erased? Keep telling the stories.

Two or three weeks ago, I was really wanting to share a big and encouraging update full of information about my new, official epilepsy update!

Yeah, that’s not going to happen. Still no diagnosis for this shaky lady. It’s not all bad news, and there is progress, but …sigh… I felt pretty low after my follow-up appointment. So, what do I know? Basically, not much.

,

The ambulatory EEG didn’t pick up any epileptic activity while I was experiencing symptoms. This is very common during focal aware seizures, which is what I am most likely having. They can affect only a tiny part of the brain and that can be hard to catch. Additionally, my symptoms experienced during the study were fairly mild; I’ve had much stronger. The next step is additional medication. It’s being added incrementally and should reduce seizure symptoms. So, if it does – yay! – focal aware seizures it is!!! If not, it looks like I may have developed some kind of headache disorder. Evidently there is a significant overlap on the Venn diagram comparing the two. Migraines, or the like, are not a desired diagnosis as that just would be another thing to have to deal with. No thank you. Looking into a comparison of both, I am confident enough I’m experiencing focal aware seizures to tell people who ask that is what’s going on. It not being official is frustrating, but I understand why the neurologist can’t give me an official diagnosis yet. The data is too qualitative. They need to make sure they’ve verified everything. And I respect that. Now that I’ve reached the end, what are focal aware seizures exactly? They are a form of partial seizure that affects, as the name implies, only part of the brain. The person also maintains a certain amount of awareness. The auras many people experience before a large seizure are a focal aware seizure that eventually expand to affect the whole brain. However, they don’t always do this. The symptoms of a focal aware seizure vary with the person and with it’s focal point within the brain. Very often, it’s a strong feeling of déjà vu or jamais vu. I have this. It’s weird, disorienting and scary. If, as a child, you ever had a really high fever, and, that night, you had a hallucinating nightnmare about Mary Poppins , that's the kind of disorienting and scary I'm talking about. Sometimes words get really hard. I can’t form them or find them. Picture a brain fart with constipation. Words can also suddenly change their meaning and spelling, so my sentences no longer make sense. Other symptoms include strange acts of clumsiness, absentmindedness, or feelings of numb tingles. In summary, brains are weird. It’s no wonder that it takes time to figure out what’s going on.

Years ago, in the early days of Facebook, I posted every day. At the time, it gave the prompt, “[Name] is…” and you would complete the sentence with whatever it is you be ising. I approached the prompt as a sort of word game and rather enjoyed the challenge of making my thoughts grammatically correct.

Then one day, I went on a hike along the bluffs of the Missouri River. I noticed that I had begun narrating my experience as Facebook updates. “Dorothy is hoping no one saw her trip on that rock,” or “Dorothy is looking down on the birds flying below.” At first I was excited to have so many post ideas, but as the day progressed, I became uncomfortable. Why couldn’t I simply be in the moment and enjoy it for myself? After that, I stopped posting every day. I would occasionally try to be more intentional about posting for the community of it all, but I really don’t like how it takes over my thoughts. I had a similar but less intense experience with Instagram (which, to be honest, is more my style and I regret not joining earlier), but since it’s switched to emphasizing Reels, not posting pictures is easy. I say all this, while at the same time, I am a person who really enjoys sharing what I notice with other people. I do this on the small scale with personal messages, and I would like to send more. I also see the appeal of making short videos and posts. I have ideas for things to write and create all of the time. But…I don’t like the social media atmosphere. I don’t want to be thinking about how people will respond before I even get started. It’s funny, in many ways, I’m unconcerned about what people think of me. And yet… In short, I’m someone who avoids attention, but gets discouraged by lack of acknowledgement. Add in wanting to avoid having posts and sharing take over my mental life, it makes sense that I’m not an active poster.

I’ve been thinking about this a lot lately because I know I could benefit from the discipling of sharing regularly. On a personal level, I’ve been in a dysregulated tumult since mid-December (see previous post). Writing about my progress and setbacks would likely help me gain more stability. It might help others, too, but I’m not in a place where that should be my focus.

On a more universal level, there’s a lot of concerning and confusing things taking place right now. I’m in a unique position of having interacted with many of the conflicting groups. I think a lot about simply telling stories about the things I’ve learned and experienced. This feels heavier and more important than writing about my health. I feel a tension between wanting to do justice to the stories shared while being 100% okay if no one ever hears what I have to say. To summarize, I am simultaneously holding the understanding that this will benefit me personally, concerns about presentation to an audience, apathy about an audience reaction, and feelings of pointlessness if no one sees it. Rather ironic to post all this on a blog that nobody reads. However, a routine posting schedule here is also the best place to start. So future person, how did I do? Christmas was yesterday, and the day was lovely. Quiet and relaxed. December has been a challenging month, with several moments of loss, sadness, and disappointment. At the same time, right now, today, I feel like the optimism I described in my previous entry maybe wasn’t such a waste of energy after all. Nothing has actually happened yet, no visible fruit, but all the same, things free more on track than they have in ages.

First, at Cage Free Voices, concrete deals are solidifying. It’s still too early to announce all the details, but after a rather tumultuous year, there are strong indications of some steadiness. We have contracts with people who are willing and able to follow through with their promises. We will be busy, very busy, but will finally, hopefully, have the space to work on the projects we most want to pursue. As with many startups, we’ve been having to pour most of our time into all the things required for survival instead of the things we enjoy. There are still risks, nothing is ever guaranteed, but there is a rightness to the way things seem to be coming together that is very reassuring. Second, two of my favorite people appear to be coming out of dark seasons. One experienced a huge blow last spring that completely undermined their confidence and led them to retreat from the world. In the past several weeks, they’ve started reentering life and interacting with others. It’s wonderful. The other had also withdrawn but for reasons related to medication that left them numb. Recently, a few changes were made that should help bring vitality back. It’s early days, too soon to know the true outcome, but signs are positive. I’m excited. I want this change for them. I’m also selfishly excited for myself. I have missed these guys. Thirdly, lastly, and most weirdly, is my health. Since the episode back in September, I’ve been getting worse, and have an ambulatory EEG scheduled for the end of January. An AEEG is a 72-hour EEG you have at home, living your life. It’s been stressful because the mini events have been fairly predictable, but there weren’t available dates during the most likely windows. Then, a week ago today, I had full on seizure out of nowhere, going completely against the pattern of predictability. The episode is a story in and of itself. All I will say now is that I was about as safe as is possible, and that my brother was again the hero of the moment. The important thing for this entry is that all the worries about the timing of the test and whether or not I’ve been overreacting to feeling off have dissipated. I can’t control this thing, and it will be okay. Yes, there are some huge questions and concerns, but steps are already in place for me to get the right help. This is complicated enough without me adding extra problems. It will be okay. So, yeah, I’m feeling optimistic. Judging from the addled state of my brain, this may be foolish, but I’ll take it! |

Dynamic DJRI write about whatever happens to be on my mind. If you'd like a bit of backstory, check out my previous blog that I haven't yet figured out how to integrate with this site. Archives

December 2025

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed